Psychology of Jurors in the Age of Coronavirus

Jury trials are “paused” in light of the Coronavirus pandemic. We know that a profound universal experience is bound to have psychological repercussions after the crisis has passed and the worldview of those who will eventually serve as jurors will likely be different when those trials resume. How do we as jury psychologists think these potential jurors will be changed? We can only surmise of course, especially since the parameters of the pandemic and its affects change almost every day. But as psychologists we do know generally about how people deal with crises and anxieties and how they deal with the threats of a significant nature. We are familiar with many personality strengths and potential weaknesses that may emerge under stress. Though this is not based on data at this point, this article posits a few theories about the psychological fallout of this pandemic.

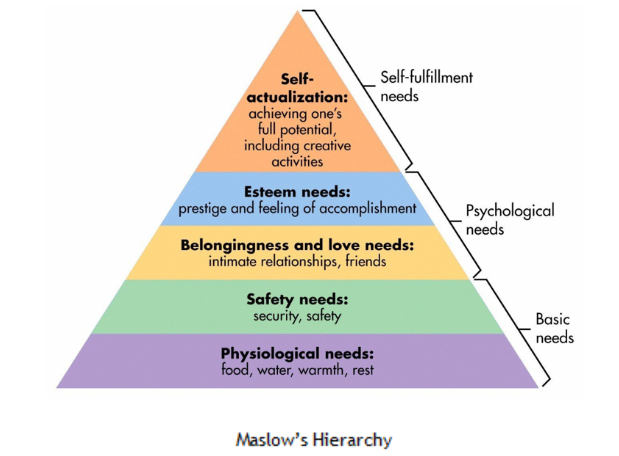

DURING THE PANDEMIC (AND PERHAPS AFTER) MASLOW’S HIERARCHY WILL RULE

Maslow’s hierarchy indicates that the first needs we humans have to satisfy are our basic needs such as food, water, warmth and rest. We will also worry most about security and safety from illness and even death. While we still have our need to belong and to be loved, the need to get those basic physical needs met becomes more important (note the hoarding that happened as the crisis mounted). As the fear that grocery stores will have no food dissipates, and as long as people can keep their homes or return to a job, fears will subside (we hope there will be jobs for all). However, those of us old enough to have had parents who lived through WWII remember that those feelings, especially if experienced when young, will often persist into adulthood, being expressed in carry–over behaviors like never throwing anything away, rationing pleasure and being grateful for every morsel on their plates (and making us as kids eat everything on those plates as well).

Safety needs regarding the virus will likely only subside when the announcements about everything from not having enough medical equipment through the numbers of deaths have stopped being the top stories on the internet. Once things are under control and people are freer to move about, these needs will give way to more press for social contact through the needs for self-esteem and self-actualization. It appears we are a long time away from this right now.

On the brighter side, there are glimmers of our humanity in our advertisements, our neighborhood chat boards and during our virtual meetings. We have also seen that human flaws make us vulnerable to some negative ways to deal with uncertainty. Here are some of the ways that we can imagine that jurors in the future will have changed based on this shared experience.

People will recognize that we are all in life together. The most likely outcome of a universal crisis is that people will be more aware of their sense of community, and many will distinguish themselves in this regard as they practice social distancing, by making donations to help families in need and even turn businesses into ways to help others. Tonight, a story about a local bar/distillery using its facilities and off products to make hand sanitizers for emergency workers is an example of working for the betterment of others. The presence of a life–threatening virus means that people may realize that one person cannot exist alone without the support of others. This sense of interdependence in a trial could be a plus for plaintiffs who are focusing on when an injury occurs or a contract is broken, but it can also be an opportunity for defendants who are trying to focus on cooperation and agreements that recognize one party’s reliance on another.

Truth may become more important. There seems to be less tolerance for information that is not real during the age of Coronavirus. While “fake news” has been thrown about as a phrase, there may be more demands for expertise and knowledge from experts rather than politicians. Attempts to cover up the truth about a bad situation are recognized for just what they are, “propaganda,” used to downplay what is a very serious situation. No one wants bad news, but there may be less tolerance for glossing over or pretending the situation is better than it is. Jurors have always wanted to be told the truth with supporting documents or information and do not want to be marketed to (e.g., the CEO who is so in love with his case that he tries to sell it to the jury) or to hear statements that witnesses make that appear to be coverups or lies (the original believability or “smell test”). Jurors in the future could demand even more evidence of what happened, why it needed to happen that way, or perhaps how it come have been prevented. Experts could be more revered. And, hindsight which has always played a role in trials may be more prevalent. Now, however, jurors may be sensitized as to “who knew what when” especially when some politicians seem to have known more (example about the state of the stock market) than other people in the world.

Empathy could be more pronounced: “It could be me.” Many potential jurors may have a sense of fear that this could affect them or their loved ones; this is a vulnerability that transcends typical worry. Many people who have never been in a situation like this may be experiencing this sense of empathy for the first time. Others who are more sympathetic will be even more likely to feel sad for those afflicted by the disease and devastated for those who have died. The fact that they fear that they could have been affected by the pandemic could last long after the actual pandemic is an issue. If denial does not take over, and the individual does not possess a narcissistic personality disorder, then trials of the future will have to deal with jurors with this increased sense of vulnerability when creating themes to offer to jurors. Plaintiff attorneys take note, as the sense of empathy, which cannot be stated directly at trial (how would you feel in this situation?) could be more positive for plaintiff cases than defense cases in the future.

Anxiety could take over. When people are anxious, they are often more likely to get angry, to be less patient and to be more interested in moving to quicker conclusions than when they are not as anxious. Anxiety breeds contempt for anyone who does not agree with an individual’s interpretation of the situation at hand. Gaps in information end up creating anxiety because there is a lack of confirmation of the situation. With COVID-19, steps to be taken are vague, the future is not clear and the worst of possibilities, illness and death, loom over families. We know that in jury trials, when there is no information, that means that people will fill the gap with their own interpretations, their own personal stories and their own potential fears. Jury trials in the future may see a greater need to show that A causes (or doesn’t cause) B and that is the only interpretation possible. Jurors who are anxious about their safety, almost always give more damages, especially if they may be influenced by future anxiety or fear.

Denial may become a strategy for some. On the other hand, many potential jurors may be in denial in the face of fears of the Coronavirus. They may put on a brave face, take chances that they deem dangerous but desirable to feel alive, or even to take chances they deem necessary to show no fear. Those who choose not to social distance may do it more out of denial than anti-social tendencies. “If I am not afraid, it will not hurt me.” Those who are following the rules could be condemned by those risk-takers as giving in to fear or letting anxiety rule their world. It remains to be seen if being brave and ignoring the social distancing norms will help or hurt these potential jurors. If they survive, they may espouse more of a personal responsibility or “survival of the fittest” mentality, which even some TV pundits have said out loud. They may be even more reluctant to believe that anyone needs to be helped, and rather that “the strong will survive.” Further research suggests that the wealthy may be susceptible to denial in this pandemic. Studies by Piff and his colleagues at UC Berkeley, “show that an increase in wealth can lead to decreases in compassion, empathy, and even willingness to obey the law.” (Landis, 2019). People who become jurors could have a sense, if they are not affected by the Coronavirus, or took chances during the worst of COVID-19, that they are invincible or that only the weak have problems or issues. This attitude would not be favorable for a plaintiff in most cases, as personal responsibility (and entitlement) attitudes often predict defense verdicts.

More conformity could appear. As a society, the U.S. has always been considered more individualistic, that is supporting diversity of opinions and deviations, than some other Eastern cultures (Japan, China) which have more collectivist attitudes (prioritizing group conformity). A recent article in Forbes (March, 2020), by Mark Travers, discusses research in cultural psychology which suggests that Americans may feel the pressure to conform, for example, agreeing to social distancing to protect others, such as the elderly. Individuals may even become more likely to call out those who do not conform, for example by telling people to keep their distance or feel the need to judge those who travel. Some of this will translate to the desire to police anyone who does not conform, such as individuals who are having parties or gatherings. This focus on the rules and following them could easily find their way into the courtrooms of the future, particularly in criminal trials, but also in trials involving those who have transgressed by not following community norms or rules. Examples could be found in environmental, contract and government regulations cases.

Fear of the out-group. In a corollary, Travers suggests that there will be another consequence of the Coronavirus, that is a rise in xenophobia. Collectivists are more wary of contact with foreigners and other out-group members. Travers suggests that growing xenophobia is seen in referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.” The fear of out-groups was already growing, for example, as seen in the coverage of the rise of in white supremacy in the United States and the belief that some people are not “real Americans.” The Coronavirus will exacerbate those fears of “the other,” and the us-versus-them mentality may intensify as the disease continues to spread (Travers, 2020). It is easy to see that in-group versus out-group attitudes have always been a part of our judicial system, but these attitudes may become more pronounced in venues in which the virus has hit hard and which already had distinct groups of disparate populations.

Self-interest could become more apparent. Alternately, self-interest even apart from the group could emerge. In situations in which there is stress or anxiety, there is often more self-interest or sense of self-protection. As noted above in Maslow’s hierarchy, people may hoard toilet paper or hand sanitizers, they may even stash them in their garages to sell to others at a scalper’s price. These individuals have most likely been self-interested or even narcissistic (pathologically self-interested) long before the outbreak, but it could be even more apparent in the years ahead. It is possible that if an individual who has shown this kind of bravado experiences a death or illness in their own family, or a close call themselves, they could have a different outlook on life, but it is not likely if this life-orientation is a personality disorder. This kind of self-interest and ego protectiveness does not usually succumb to life experience or to therapy. In addition, studies suggest another group of self-focused individuals are the wealthy. While you might think that wealth might increase feelings of generosity and compassion, and that having less would lead to a greater level of selfishness, wealth appears to increase a sense of entitlement and narcissism. Piff (2014) at UC Berkeley, suggest that this true because wealth and abundance give one more independence and personal choice. The less individuals must rely on others, the more they tend to be more self-focused. Self-centeredness means people are less likely to feel for individuals who have been hurt and more likely that they will still identify with power and control, thus will be better jurors for defendants in the future.

Control issues will emerge. Some people have issues with control—in fact, most of us do. Some of these issues have to do with the need to control oneself and/or to control others, usually to deal with anxiety (and in some cases self-esteem). We can probably see these “control issues” in each other. Some people need to count cans of beans in the pantry to feel safe. They need to tell other people not to stand too close in the store. Some just want to make sure the store allows them to self-check out and do not care what other people do. A person who needs control needs structure. They need to see the police enforcing rules and people only being allowed to take two loaves of bread. It is likely these control needs could be displayed in the courtroom. Jurors who need control will focus on the law, will not like rule-breakers, and will usually find for whichever party appears to have made the least mistakes.

A different sense of control is called locus of control, originally defined by Julian Rotter in 1956. Locus of control is the degree to which someone believes that they have control (as opposed to outside forces) over the outcome of events in their lives. Someone with an internal locus of control has a belief that they can control their own life, as compared to someone who has an external locus of control which is a belief that life is controlled by outside factors which the person cannot influence, or that chance or fate controls their lives. Individuals with an internal locus of control are much more likely to have less stress during this crisis and may be more likely to take all precautions to prevent contracting or spreading the virus feeling that these changes can make a difference. Those with an external locus of control are more likely to believe that fate will control what happens to them and even that they have no ability to do anything to change the outcome for themselves. This would be consistent with research on the effects of locus of control on health. While a pandemic like this one challenges anyone’s sense of control over their environment, it will certainly affect more people short and long term than others. Those who enter the courtroom as a juror with an internal locus of control may find they believe that individuals control their destinies more than those with an external locus of control, but post-pandemic, this could depend on the way that they perceive the outcome of the pandemic for themselves and others.

IN CONCLUSION

The population’s response to the Coronavirus is ripe for study as we determine which attitudes are activated and how they interact with individuals’ personality characteristics. As psychologists and jury consultants we will watch the unfolding psychology which might affect perceptions of the parties in a lawsuit, the witnesses they would want to hear from, the themes that may be more persuasive and the ways that we can predict which type of jurors will react favorably and unfavorably to your case.

In the meantime, stay safe, healthy and keep a positive outlook.

REFERENCES

McLeod, S. A. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply psychology: https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Landes, L. (2019) Wealthy People are Mean, Entitled and Narcissistic – Consumerism Commentary. http://consumerismcommentary.com/wealthy-mean-entitled/

Manne, A. (2014). The age of entitlement: how wealth breeds narcissism. The Guardian, July7. https;//www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/July08/the-age-of-entitlement-how-wealth-breeds-narcissism

Piff, P. K. (2014). Wealth and the inflated self: Class, entitlement, and narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 34-43.

Rotter, Julian B (1966). “Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement”. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied. 80: 1–28. doi:10.1037/h0092976.

Travers, M. (2020). Cultural psychology research suggests the U.S. may be less individualistic after Coronavirus. Forbes, March 23, 2020.